Photo credit: Council of State Governments

By Hunter Marion.

On August 16th, 2022, President Biden signed into law the largest, most comprehensive environmental bill in our country’s history, the Inflation Reduction Act (2022). It might even be more impactful than the milestone environmental legislation passed during the 1970s.

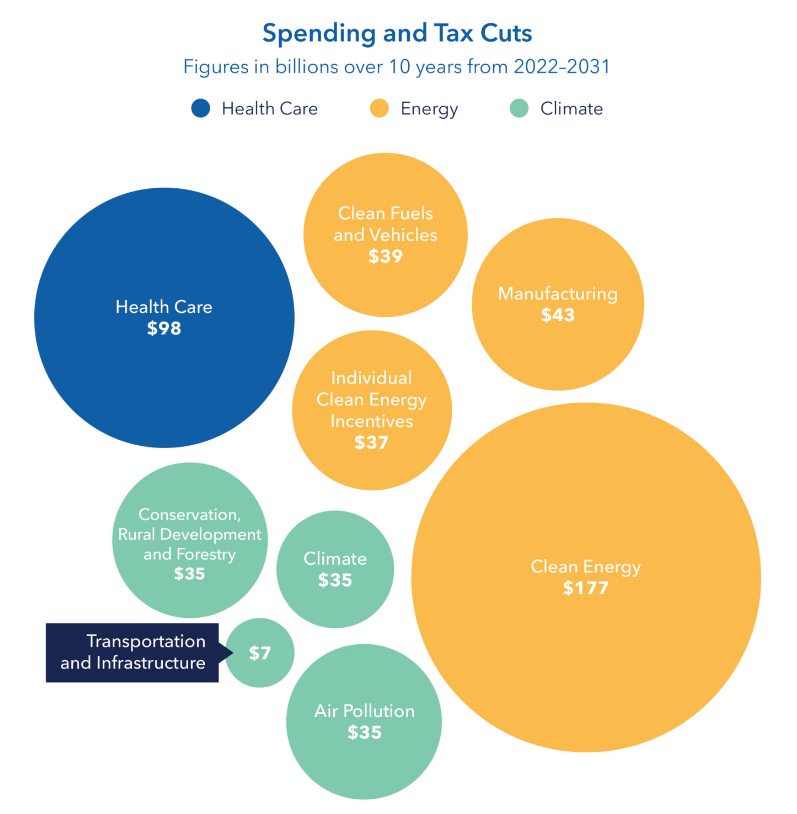

The IRA is a massive bill, encompassing a mind-boggling list of new laws ranging from prescription drug regulation to rejuvenating the IRS to environmental justice to agricultural carbon sequestration to the Justice40 Initiative. It is packed with new policies, tax credits, and grants determined to simultaneously reduce future economic downturn and bolster the United States as the world’s frontrunner in green technology and environmentalism. As exciting and momentous an achievement as this is within the environmental movement, it is not immune to criticism.

Without a doubt, the IRA is full of marvelous carrots designed to incentivize compliance. It provides plentiful tax credits and rebates to taxpayers and companies who buy into or transition to cleaner technologies, like electric appliances, EVs, or renewable energy sources. Low-income or BIPOC grassroots groups and EJ communities can access more readily available funding for air monitoring technology, technical assistance, urban forestry, and more. Even government contractors can see their subsidized budgets and clientele sizably increase if they comply to prevailing wage and apprenticeship guidelines. However, this bill is surprisingly limited on sticks.

The sticks that are present do have potential to make meaningful environmental changes. For instance, the IRA taxes corporations at a much higher rate for leaking methane, holding a land lease without developing it, or refusing to comply with renewable energy transitions. The Superfund excise tax (which was reinstated in 2021) has even been applied to crude oil/petroleum products and a list of chemical substances, including two PFAS. (Polyfluoroalkyl substances, or “PFAS,” are extremely pervasive and long-lasting chemicals or microplastics known to be harmful to human health). Nevertheless, for a bill determined to lower national greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to pre-2005 levels, it hesitates to give the oil and gas (O&G) industry a slap on the wrist. It even provides hearty kickbacks to the O&G industry, such as authorizing the lease of previously unavailable offshore wells in Alaska and the Gulf Coast and allowing extraction wells to be located nearby (or preferred over) wind or solar farms.

Along with failing to directly limit O&G, this bill also ignores a few key battles within the environmental movement. First, hazardous fracking waste regulation is absent from the bill. As detailed in my previous blog, orphaned radioactive fracking waste is a national issue that falls through the cracks of most state and federal regulatory agencies. Second, the PFAS that are included in the renewed Superfund chemicals list are “legacy” PFAS. They are no longer manufactured (some stopped being made over 15 years ago) but still have significant presence within EJ communities. Despite their inclusion being a success to these groups, it belies the fact that hundreds of other similarly dangerous PFAS are still being synthesized and sold without much regulation. Lastly, the Civilian Climate Corps (CCC), a program intended to put restoration and conservation efforts directly into the hands of community members, was absent from the finalized bill. The Biden Administration designed the CCC to be a climate-based government program modeled after the New Deal-era Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) or Civil Works Administration (CWA). It was a revitalized effort to make environmentalism and community decision-making accessible for lower-wealth, BIPOC, and young people. Sadly, those plans fell through at the last minute. In fairness, it is truly remarkable that this bill passed at all, especially since its authority is uncertain.

As of late, the U.S. Supreme Court has been set on undermining crucial environmental regulations. In West Virginia v. EPA (2022), SCOTUS ruled that the EPA could not put state-level caps on carbon emissions under the Clean Air Act. In Sackett v. EPA (2023), SCOTUS is likely to rule in favor of reducing protections of wetlands and waterways harbored under the Clean Water Act. It would not be any surprise if a case against one of the hundreds of policies contained in the IRA made its way to the Supreme Court. Nor would it be a shock if they too ruled in favor of dismantling a central component to these new environmental laws. The good news, however, is that this would likely be a decades-long process due to the copious number of laws and policies included in this bill. Now, if an anti-environmentalist collective were to gain the majority in the U.S. Congress in a future election cycle, that would be a different story.

No matter how likely a retaliation to this bill is or how much it is missing, it does not invalidate the small joy of watching the U.S. try to take a huge step towards becoming a greener, cleaner country. However, we must acknowledge that this bill does not nearly satisfy environmentalists’ demands, especially with Sen. Manchin’s “Dirty Bill” looming over it.

To learn more about the Inflation Reduction Act, check out this informative video by Hank Green of the VlogBrothers.