Superfund

Table of Contents

What is Superfund?

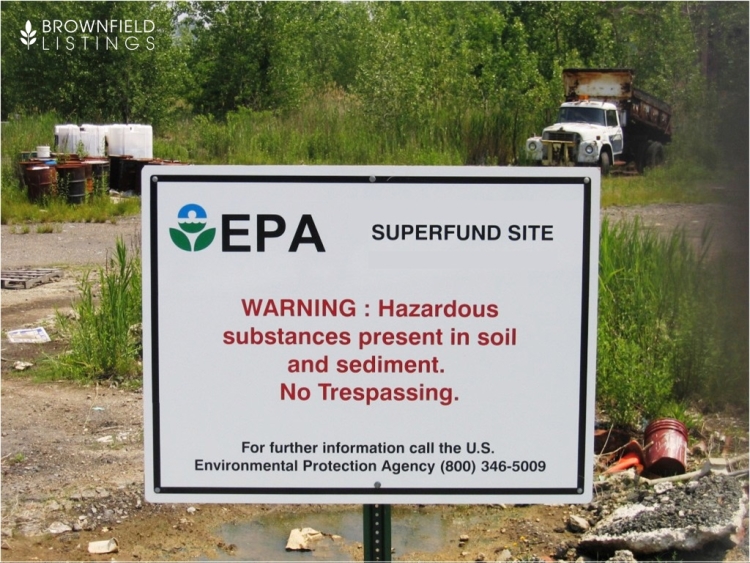

- The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980, or Superfund, is designed to grant authority to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), states and Native American nations to manage and clean up the United States’ most dangerous waste sites.

- Superfund gives the EPA the responsibility to address acute local and national environmental emergencies that threaten public health and the environment.

- Most importantly, Superfund creates a system where polluters have to pay for the messes they create. The EPA identifies the potentially responsible parties (PRPs) that created hazardous sites and requires them to fund and/or manage the cleanups.

What is the history of Superfund?

- CERCLA came into existence after a State of Emergency was declared at Love Canal, New York in 1978. The act includes a retroactive liability provision that allows the EPA to hold past parties that created dangerous waste sites accountable for clean-up. Around 70% of Superfund cleanups have been paid by responsible parties.

-

People of color, immigrants, and low-income people are overrepresented in communities near Superfund sites. Historically, and to this day, polluters have deliberately targeted these communities when deciding where to dump waste.

What is the Polluters Pay fee and why isn’t it being collected?

- The Polluters Pay fee is one of the ways Superfund ensures that people responsible for pollution fund its clean up. The EPA would collect a fee from the petroleum and chemical industries, which was used to fund cleanups for pollution sites that had no clearly identifiable responsible party or were polluted by bankrupt parties.

- The fee also served as a motivation to switch to less hazardous production methods.

- The tax has not been collected since 1995, however, and by 2004, there was no longer any money in the Superfund. Now, the EPA is forced to fund Superfund through taxpayer money— taxpayers are paying to clean up pollution, rather than the polluters themselves.

What is CHEJ doing to put the “Super” back in Superfund?

- Currently, CHEJ is working towards making Superfund super again by helping grassroots organizations and advocating the restoration of the Polluters Pays fees to refinance the CERCLA trust fund.

- In July 2019, Representative Earl Blumenauer (OR) introduced legislation (H.R. 4088) that would revive the tax component of the federal Superfund program and once again force industries responsible for contaminating soil, air and water to pay for the cleanup of these sites.

- This proposed law would also make funds available directly to the EPA on an ongoing basis instead of being subject to annual appropriations.

- CHEJ has also created a petition to bring back the Polluters Pay Tax, which you can sign here.